When the first volume of Spengler’s Decline of the West appeared in Germany shortly after the First World War, it was an unexpected success. At this time, Spengler’s idea that the Western civilization is slowly but inevitably entering into its last phase of ‘life’ was in the eyes of the German public confirmed by hardships of the post-war years. Moreover, it provided very much desired answers that rationalised the German post-war suffering into a context of the decline of the Western civilization itself.

When the first volume of Spengler’s Decline of the West appeared in Germany shortly after the First World War, it was an unexpected success. At this time, Spengler’s idea that the Western civilization is slowly but inevitably entering into its last phase of ‘life’ was in the eyes of the German public confirmed by hardships of the post-war years. Moreover, it provided very much desired answers that rationalised the German post-war suffering into a context of the decline of the Western civilization itself.But Spengler did not want to provide simple answers for the masses. He was also far for trying to spread pessimism. He merely presented the idea that all cultures are organic entities that go through birth, adulthood, and ultimately their death. The same life course should be expected for the Western world – for the so-called Faustian culture – Spengler believed, and this was the time of its transition from the culture to the civilization.

This transition is characterised among others things especially by migration of people from countryside to city assuring thus their separation from soil – from the experience of natural life. People, instead of experiencing what the real life is – are now separated from it in cities, leading to abstract, from real experience separated ideas and thinking.

The use of the word ‘Faustian’ when describing the Western culture Spengler explained by pointing out a parallel between the tragic figure of Faust and the Western world. Just as Faust sold his soul to the devil to gain greater power, the Western man sold his soul to technics.

It might be now quite easy to see what Spengler had in mind. We rely so much on our technological miracles that we tend to forgot that we would not be able to live without them. This is neither good, neither bad, it is the way things currently are. However, it would be foolish to describe ourselves solely as Nature’s creatures. To ‘return to Nature,’ to ‘live in harmony with it’ as perhaps Rousseau would have is an impossible nonsense, Spengler argues. With the first sparks of fire made by Man, he desires to control the unleashed power, not merely to look at it with awe. The inspiration with Nietzsche is at this point obvious.

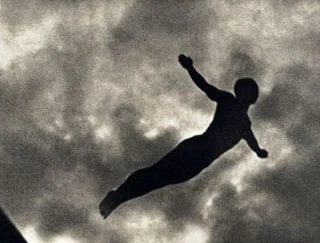

The difference between Goethe’s Faust and the Faustian man is thus only one, Spengler said, for the destiny for the latter offers no way to ‘redemption’. Spengler gives just as Julius Evola after him a parallel to a Roman centurion – the Faustian man can face the coming twilight with courage and determination and make his end spectacular, but these are all options left. The optimism must be condemned as weakness to face the inevitable.

Finally, it must be left to the reader to consider for himself whether our civilization truly faces any decline or whether the only remaining option is just to try to hold to the fading banner. What cannot be denied however is that Spengler’s writings give us a certain feeling of melancholy and we can easily imagine Spengler writing before the dusk of the First World War, predicting a tragedy which would wipe away all the things past and leave the Western man with a bleak vision of his inevitable destiny.

Except this eight hundred pages long two volume edition of Decline of the West, other Spengler’s works for instance include Man & Technics or Prussianism and Socialism, which are perhaps more accesible to the first time reader thanks to their shorter length.

Originally passed from Faustian Europe.

***

*** ***

***

Nejnovější komentáře